Who is Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and What Does He Want? Part 1

I met Ali Khamenei only once. In 1984, I was an assistant photographer, and he was the president of Iran. My boss, the prominent Iranian photographer Masoud Masoumi, had been commissioned to take a portrait. My job was to carry the camera and lights through security the day before, set everything up according to Masoud’s instructions, and then wait for the president to arrive.

By the time you read this, Ali Khamenei, who has been Iran’s “Supreme” Leader since 1989, may have died of natural causes, been killed by Israeli or American bombs, or even been murdered by one of his aides. All three scenarios are possible. But he will most likely survive this crisis, as he has so many others, and move on to lead his nation to the brink of yet another disaster.

“Who is Ali Khamenei and what does he want?” is being asked by millions of people around the world. So, over a couple of articles, I’ll try to give you, dear reader, something of what I know about him alongside anecdotes from people who know him well. I’ll try to provide you with an idea of him as a man who has the blood of civilians, from Iran and around the world, on his hands. He’s not a cartoonish one-dimensional monster.

He is a human being, someone who has overseen torture, maiming, and murder, and at the same time a great orator, a lover of literature and poetry, and who by hook or by crook has stayed in power for the past 38 years.

During my one encounter with him, I found him congenial, with a surprisingly self-deprecating sense of humor. “What’s your name, young man?” he asked, and then went on to praise the name Maziar, which in old Persian means someone who is helped by God and the moon. “Well done to your parents! Such an inspiring name!” Ali Khamenei said. “Let’s all sit down and let Mr. Maziar take care of everything, since he’s being helped by God and the moon.” He looked at the bodyguards and assistants around him and said, “Can you match the Almighty and the moon? I don’t think so. Even the tea we asked for is not here yet!”

My sister was in jail at the time, because of her political activities, and I already knew about the atrocities committed by the regime. Yet, Ali Khamenei’s charm disarmed me and, for a moment, I’m ashamed to say, I even liked him.

In 30 years of covering Iran, I’ve met hundreds of people who’ve worked with Ali Khamenei and have known him for decades. Most of the information here is in the public domain, but I’ll also share some of the private observations of people who are dead and whose intelligence goons cannot hurt anymore. I’ll also quote some anonymous sources.

The most important thing about Ali Khamenei is that he’s unpredictable and conniving. His hunger for power – and for surviving long enough to keep it – is matched by the devious (his allies call it clever) ways he undermines his rivals and enemies. In fact, the 86-year-old cleric became the political and military leader of Iran in 1989 because he tricked other, more prominent, regime leaders into thinking he was an empty vessel they could use for their own ambitions.

Thirty-seven years later, Ali Khamenei’s rivals are either dead or under house arrest. He’s the longest-serving leader in the Middle East.

Before I go any further, let me explain why I keep calling Khamenei by his full name, Ali Khamenei. In the following paragraphs, you’ll also read about Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of the 1979 Islamic Revolution and Ali Khamenei’s predecessor. So, to avoid confusing the two clerics, Kho-mei-ni and Kha-me-nei, I’ll call them Ruhollah Khomeini and Ali Khamenei.

Unlike Ruhollah Khomeini, Ali Khamenei was never an outstanding scholar or leader. Yet, used his unassuming character as a student, cleric, revolutionary, and poet to endear himself to different groups. Throughout his life, until he became the leader, Khamenei played second fiddle and seemed quite happy to do so.

“Seemed to be” is the operative term. During his leadership, Ali Khamenei has taken revenge on his rivals, methodically sidelining them one by one. In the first decade of his reign, he gained the trust of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) and intelligence apparatus, two groups he needed to be able to identify and suppress his critics and enemies. In the second decade or so, he solidified his leadership by letting everyone know that his regime would never reform its social, cultural, or political policies. And since 2009, he has aspired to be a great leader of an Islamic nation. Two decades of cronies sucking up to him has now convinced Ali Khamenei that he’s the man to guide Iran to economic independence, scientific advancements, and becoming a Middle Eastern superpower dominating its Arab rivals and Israel.

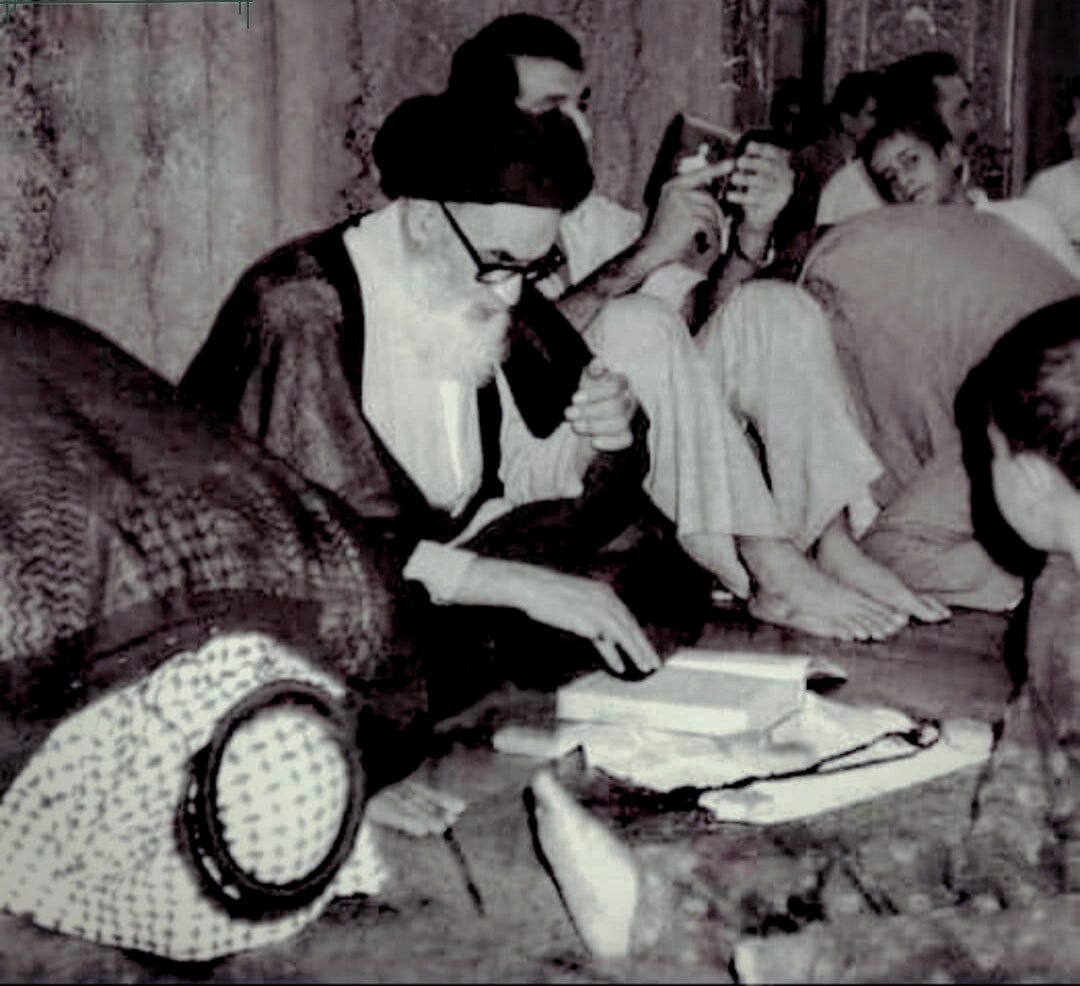

Khamenei was born in the city of Mashhad in 1939. This is a photo of him with some family members.

Mashhad is Iran’s second-largest city. It’s home to the shrine of Imam Reza, the 8th Shia imam, one of 12 descendants of the Prophet Mohammad venerated by Shia Muslims. Mashhad is a religious city, but it also has a vibrant cultural and political scene that inspired Khamenei.

According to many poets from Mashhad, the future tyrant loved to hang out with them, serve them tea, and now and then even smoke opium with them.

He didn’t have much talent for poetry, but he was a hard worker and persevered. Hard work and perseverance without talent don’t make a great poet, of course, but Ali Khamenei would draw on those qualities again as a revolutionary and then as a leader.

Even now, he likes to be regarded as the Supreme Poet and the Supreme Leader. He regularly organises poetry sessions in his office while offering younger poets feedback on their work.

Khamenei was 23 in 1962, when Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini started his movement against the Shah’s White Revolution – an attempt to modernize Iran by dividing lands owned by Iran’s landowners among farmers and giving women the right to vote.

Most Iranian clerics objected to both goals. Iranian seminaries and clerics were supported by the country’s great landowners. To most Iranian clerics, women were second-class citizens who should not have had the same rights as men. In a letter to the Shah dated November 6, 1962, Ruhollah Khomeini wrote that giving women the vote could lead to prostitution.

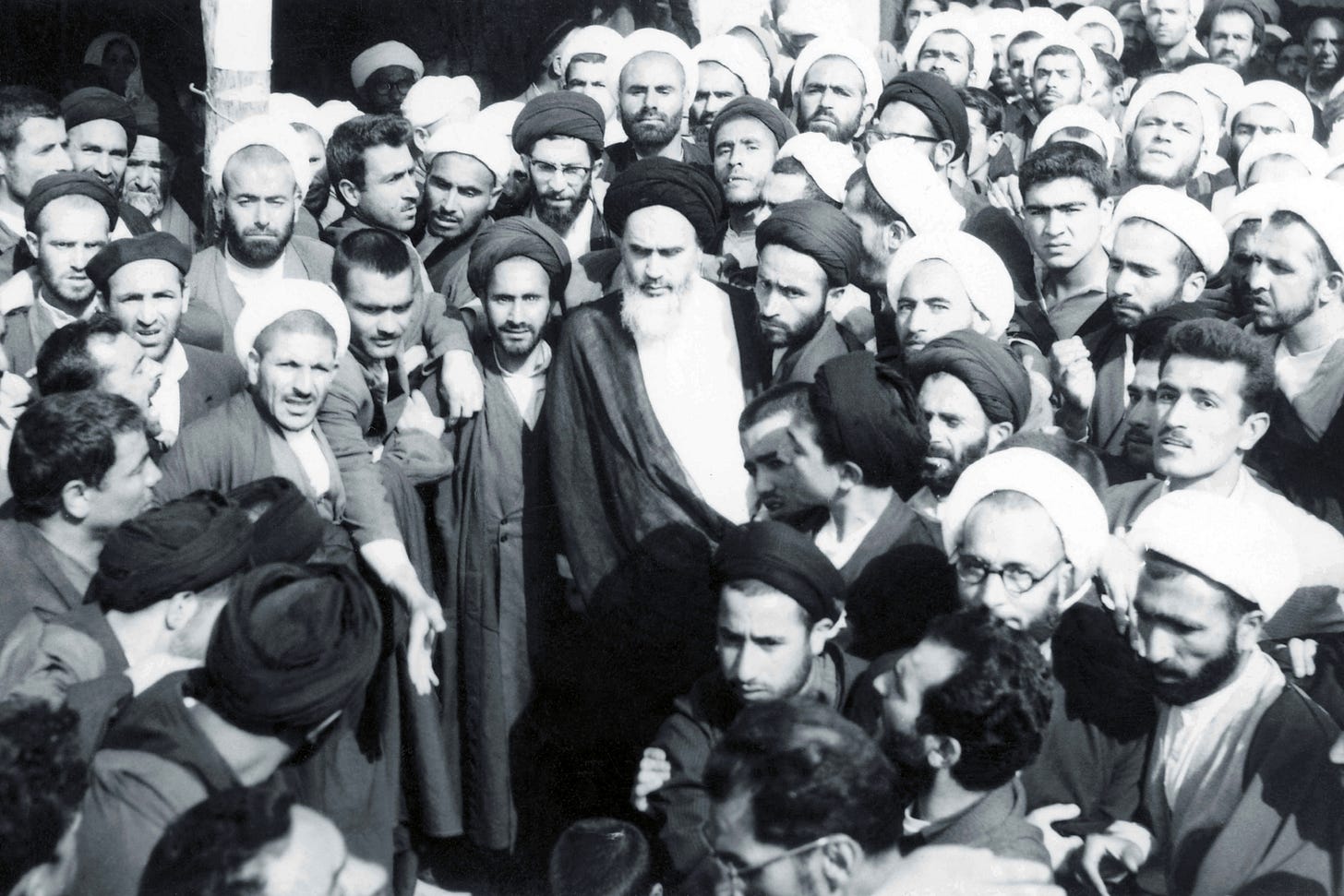

Sixty-three years later, it may sound odd that the grand ayatollah thought women would go from the ballot box to the brothel in one easy leap. However, many religious Iranians (and non-Iranians) felt the same way. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was a high-ranking and popular seminary teacher in Qom, where Saint Massouma, the sister of Imam Reza (the 8th Imam), is buried. The Ayatollah’s objections to the Shah’s actions led to a mass movement, which the Shah’s soldiers swiftly and violently crushed in June 1963.

Ruhollah Khomeini was sent into exile in 1964. He moved from Turkey to Iraq to France and communicated with his supporters through cassette tapes smuggled into Iran and photocopies of his messages.

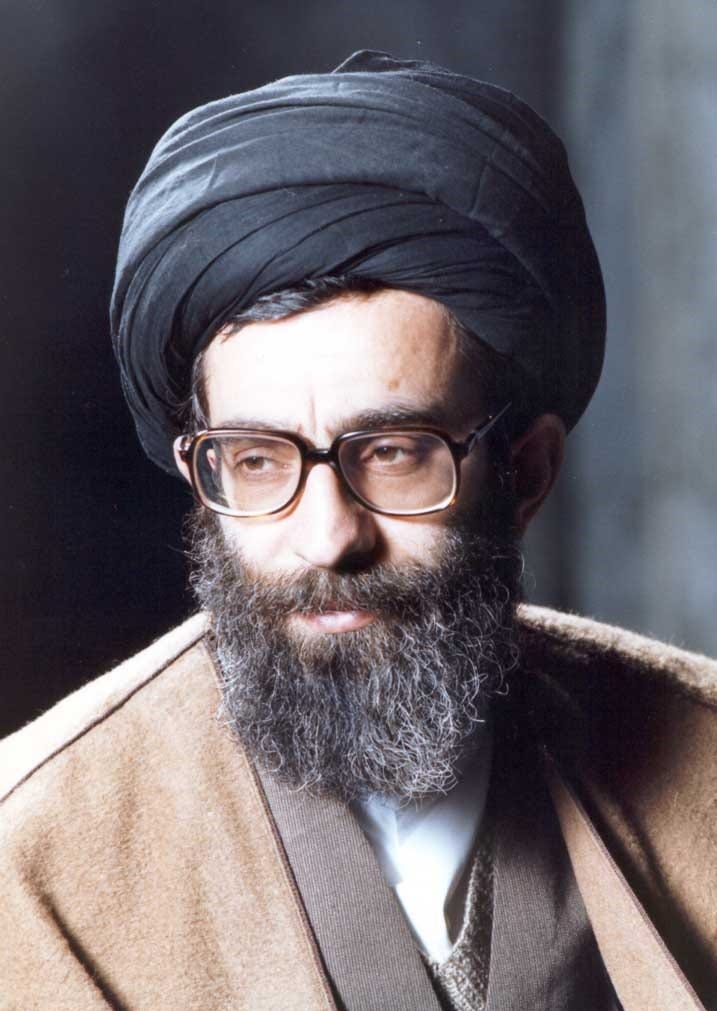

Between 1963 and 1979, as Iran became richer through high oil prices and the Shah grew in power, Ali Khamenei reduced his literary activities and dedicated himself to Khomeini’s cause. This meant he did not advance his religious studies and remained a junior cleric; he remained a “hojatolislam,” rather than a senior cleric, an “ayatollah,” until he became leader.

At the same time, far from the gaze of the Shah’s intelligence officers, the Islamic Revolution unfolded in mosques and religious centers across Iran. Ali Khamenei was among several dozen clerics who distributed Ruhollah Khomeini’s revolutionary material in Iran.

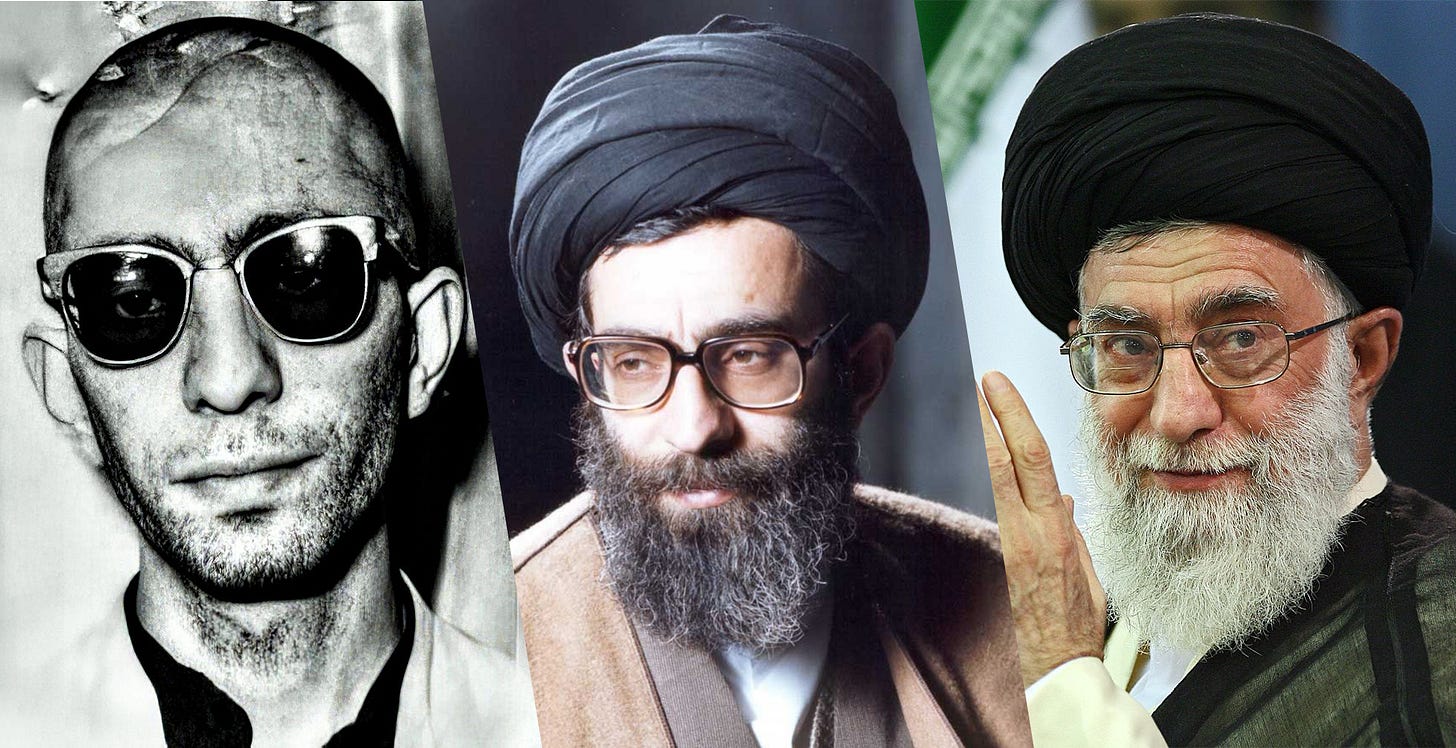

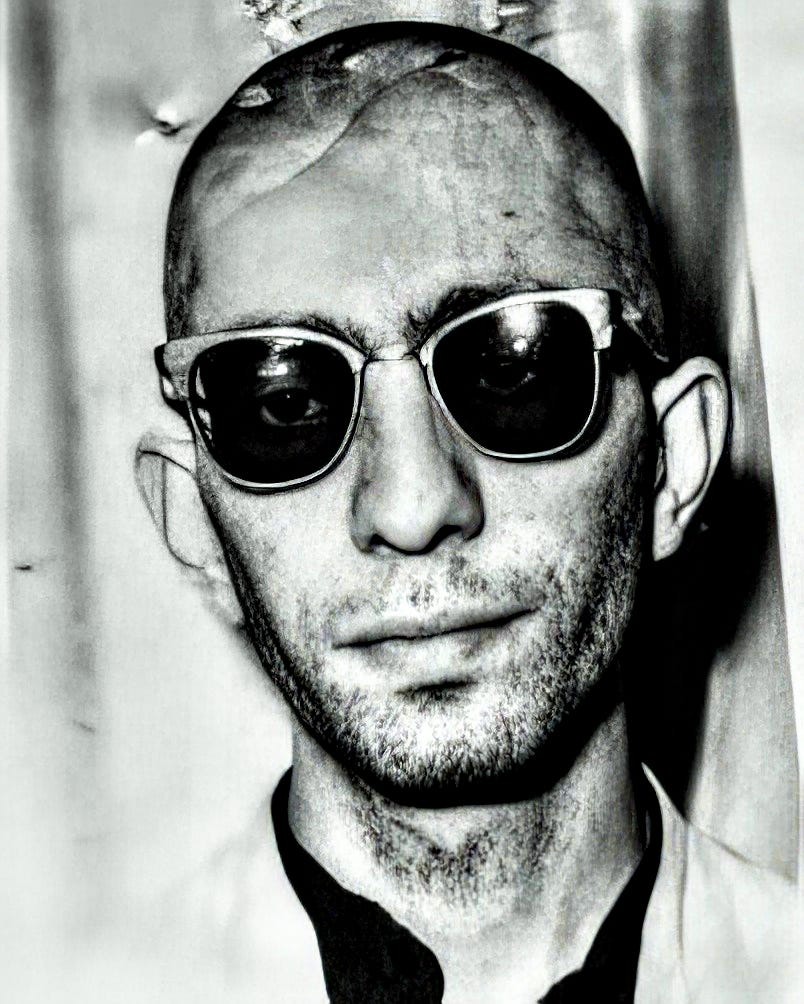

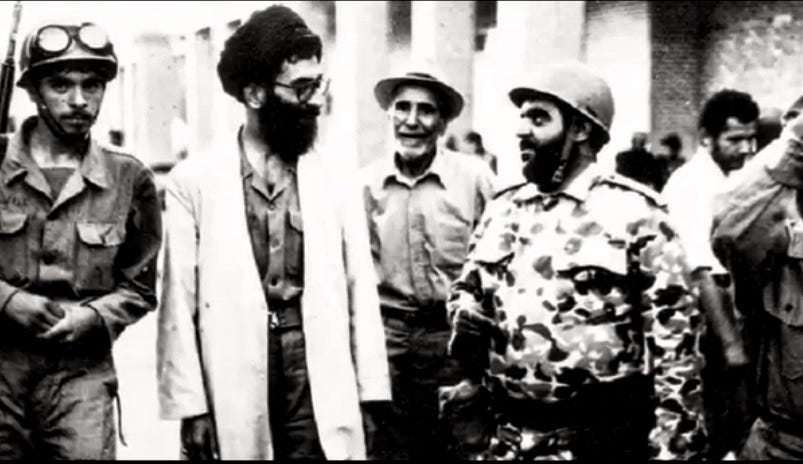

The Shah’s intelligence service, Savak, treated Islamic revolutionaries as “irrelevant,” since the Shah was more preoccupied with communist guerrillas and supporters of the Soviet Union. But Savak did still jail many followers of Ruhollah Khomeini, including on several occasions, Ali Khamenei. He was also sent into internal exile a few times. Here is the most famous picture of him as a political prisoner. He looks like an alt rocker.

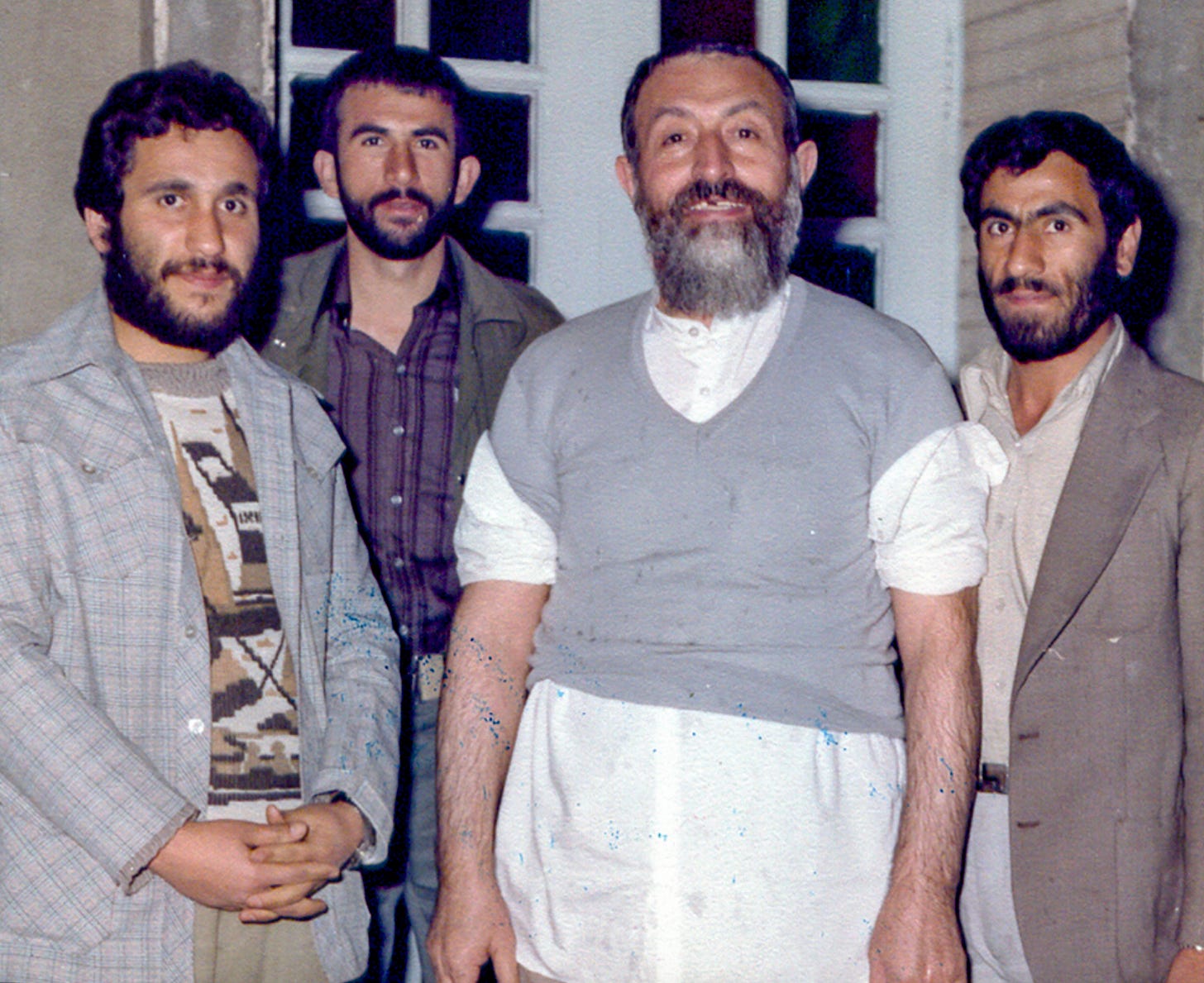

In jail, people gain a better understanding of each other’s character. They sleep, eat and hold meetings in the same small quarters. The relationships formed in jail between various groups and individuals shaped the revolution and the Islamic Republic. Many political partnerships were formed in prison, and rivalries between different groups deepened. From what we know, Ali Khamenei acted decently in prison. The Paris-based writer Houshang Assadi, who spent months with him in jail, says he was good company and a caring cellmate. And communist leader Mohammad Ali Amooee says that Ali Khamenei was among the most open-minded Muslim prisoners, and that he did not regard communists najes, or unclean, and didn’t separate his dishes from them.

In the meantime, Ruhollah Khomeini started to teach at the Najaf seminary and wrote a book called Velayateh Faqih, or the Guardianship of the Islamic Jurisprudent. In the book, he argued that a high-ranking cleric who knows Shia Islam’s laws should oversee the country's affairs, and it became the theory behind the form of government Iran has today.

Ali Khamenei is now Iran’s Valiyeh Faqih: the Supreme Jurist.

The Shah continued to ignore Ruhollah Khomeini’s increasing popularity and his network of representatives around Iran. After he was released from jail, Ali Khamenei was among those who distributed anti-Shah cassette tapes and pamphlets to many Iranians who either did not support the Shah’s ambitions of making Iran an industrialized pro-Western country, or opposed his authoritarian rule and his slogan “God, the Shah, the Country,” or in other words, protecting the Shah comes before even the country.

The Shah was diagnosed with cancer in the early 1970s, but it was never revealed to the public. He remained fiercely anti-communist and jailed or executed hundreds of communist guerrillas. Khomeini’s supporters were relatively untouched by these campaigns. Some historians believe the Shah’s illness was the main reason for his indecision and lack of judgment.

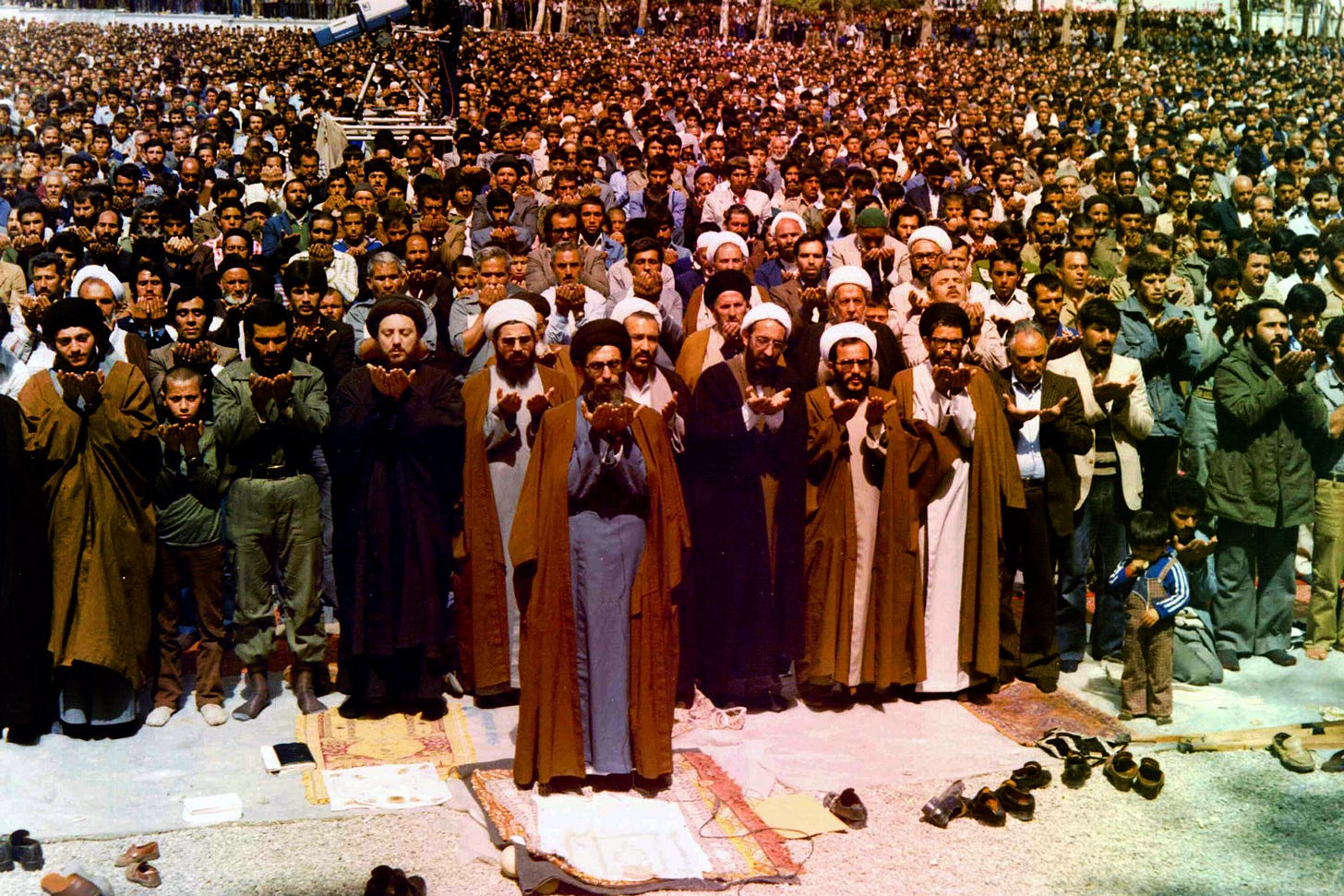

In January 1978, when a newspaper published an anti-Ruhollah Khomeini article, a group of his followers demonstrated at their seminary in Qom. In the ensuing crackdown, many of them were killed by the Shah’s army. According to Shia Islamic tradition, the dead were mourned for 40 days, and the mourning turned into protests, and even more people were killed. The same thing happened forty days later, and yet more people participated in the protests.

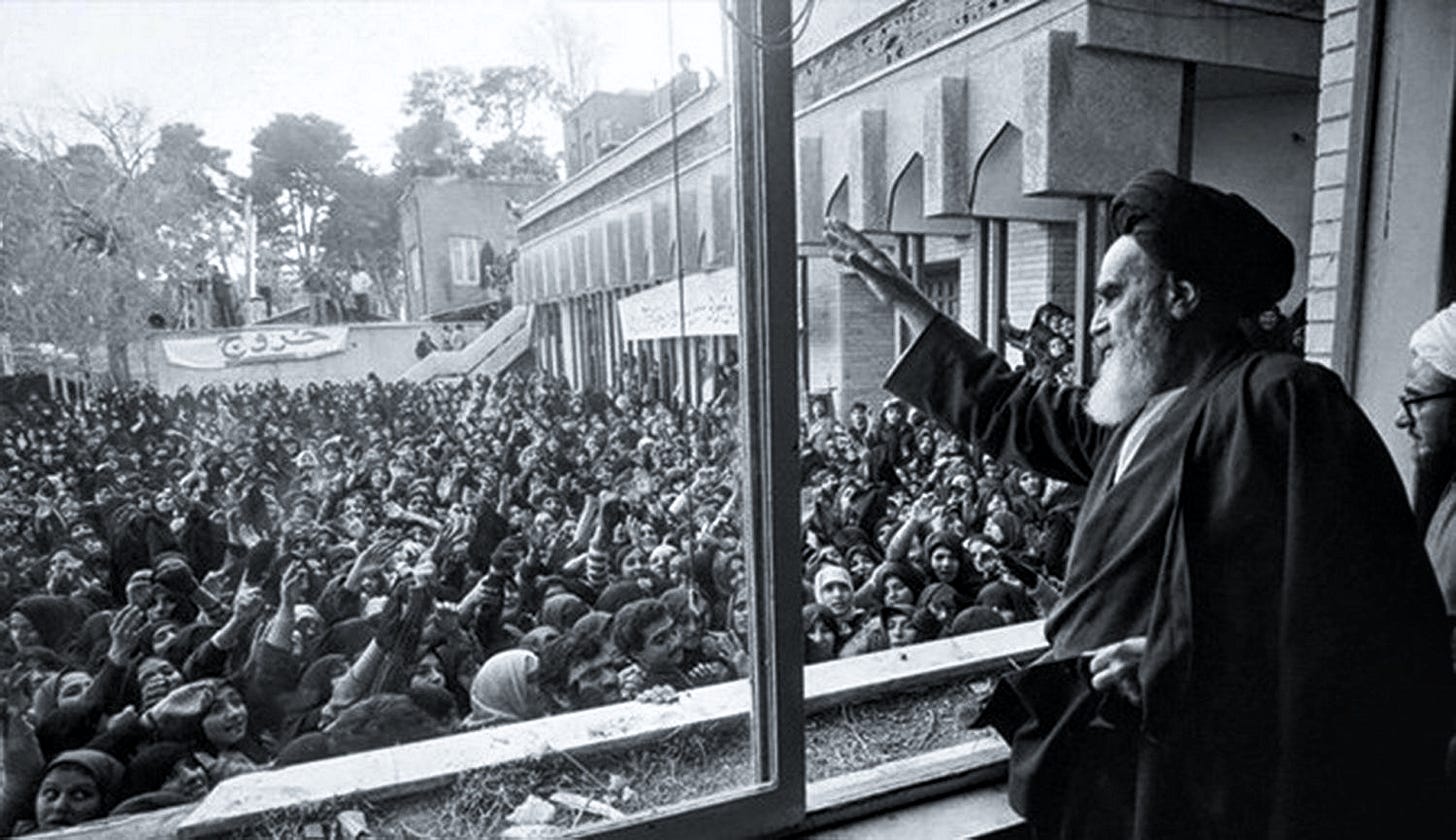

In September 1979, the Shah said he had “heard the people’s revolution,” and promised to reform his system. Too little, too late. The Shah’s regime was toppled on February 11, 1979, and Ruhollah Khomeini took on the role he had theorized in the late 1960s: the Valiyeh Faqih of Iran.

From then on, he was called Imam Khomeini.

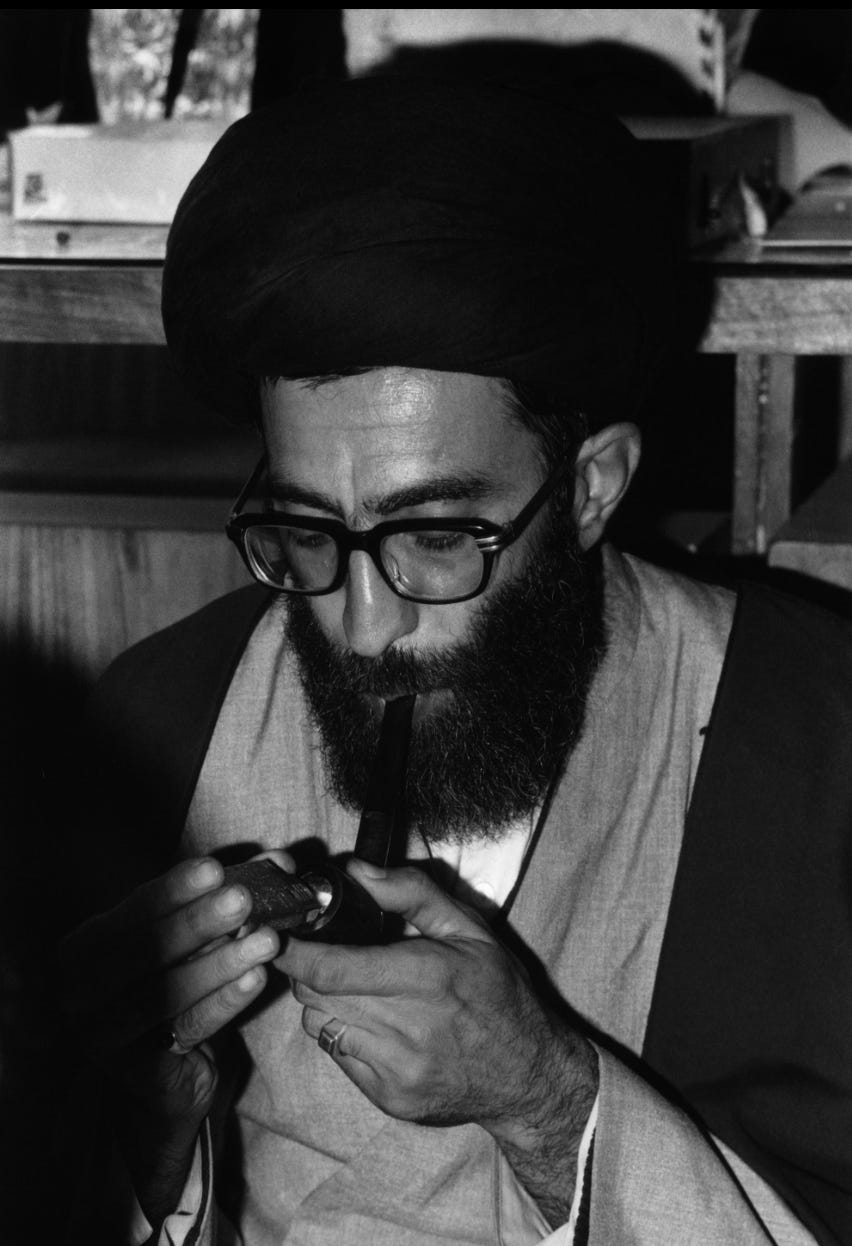

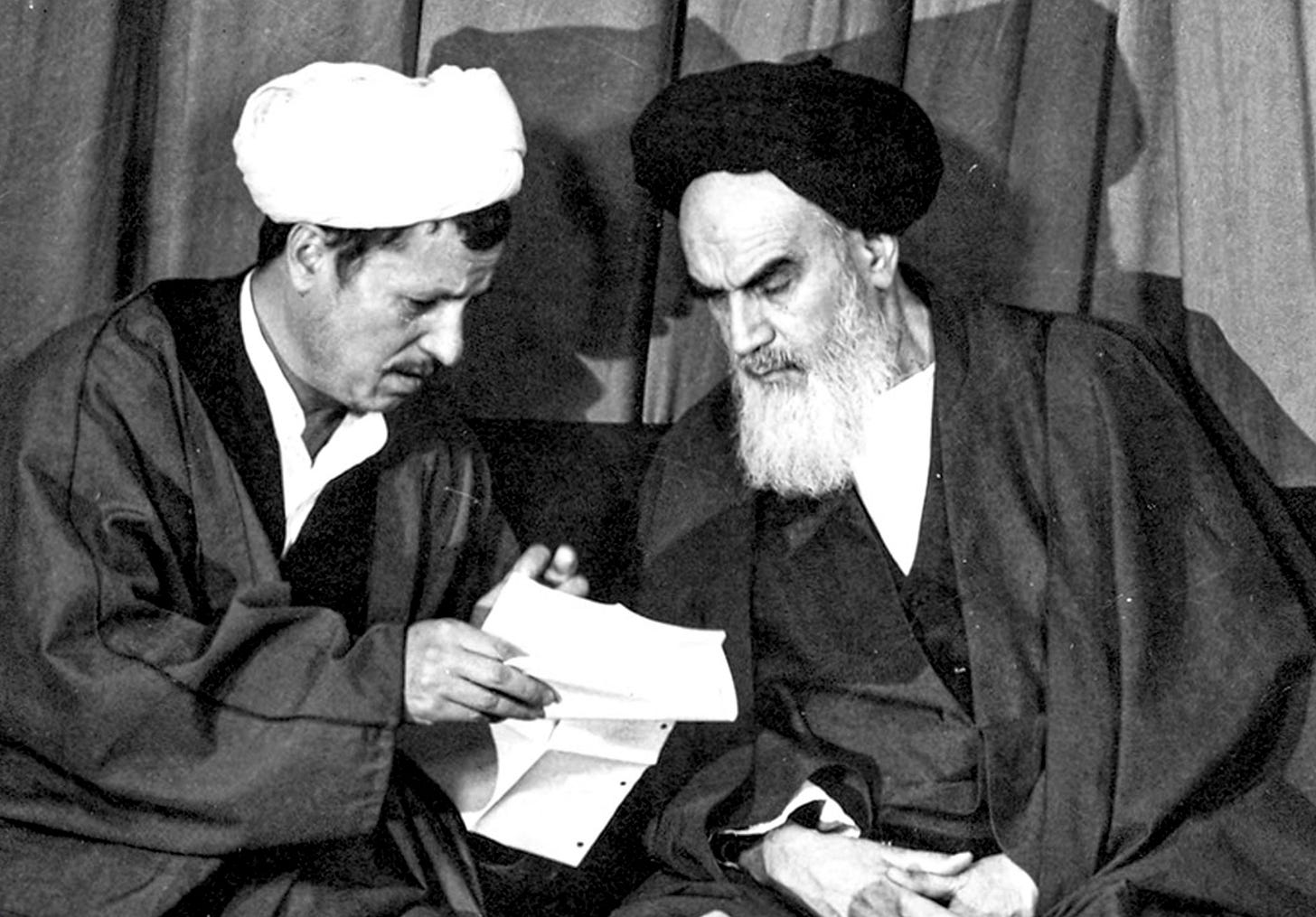

After the revolution, Ali Khamenei became one of Ruhollah Khomeini’s close aides. Ali Khamenei was regarded as a pragmatic cleric who got along well with various factions within the government and even opposition leaders. He knew many of them from their time in prison. And he continued to hang out with poets, becoming famous for his love of smoking pipes and cigarettes. The rumors about his opium addiction started around the same time.

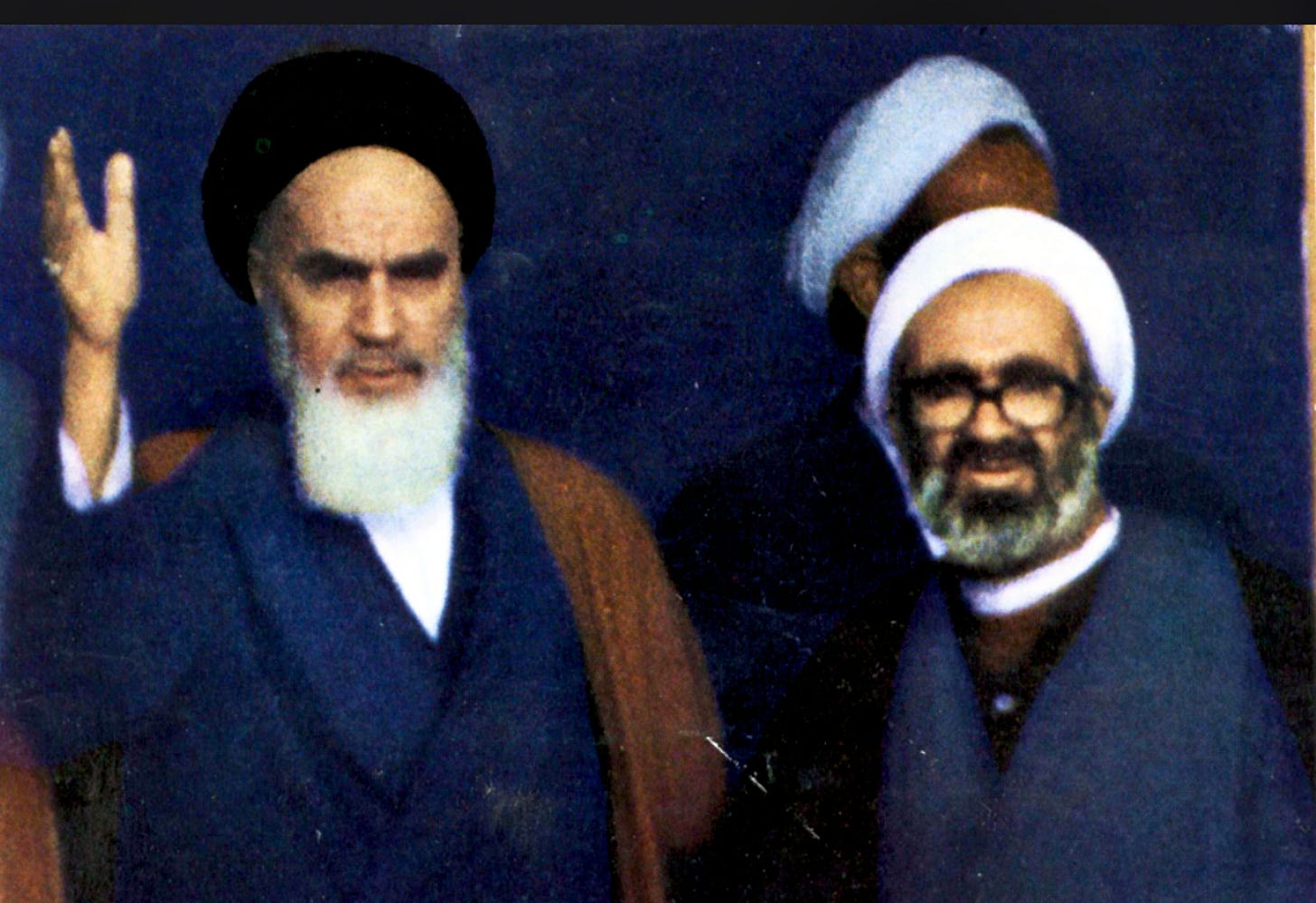

But Ali Khamenei was not among the three people within the Imam’s closest inner circle; the ayatollahs Hossein Ali Montazeri, Mohammad Beheshti, and Hojatolislam Ali Akbar Rafsanjani.

We now know that Ali Khamenei resented not being among the top three. In a 2005 interview, Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri told me that while Ali Khamenei didn’t say anything then, he continued to hold a grudge against people trusted by Ruhollah Khomeini. Many of his venomous actions as a leader were born of that grudge.

Ruhollah Khomeini had chosen Montazeri, a high-ranking ayatollah who spent many years in prison under the Shah, as his successor. Montazeri was famous for his outspokenness. And even though he was the heir apparent, Montazeri insisted on operating independently of Ruhollah Khomeini. He maintained his own inner circle and operatives across the country. His actions eventually led to a public clash with Ruhollah Khomeini.

Mohammad Hosseini Beheshti had lived in Germany before the revolution and was the most prominent member of Khomeini’s younger acolytes. Beheshti was famous for articulating the idea of the Velayateh Faqih into a set of guidelines for running a government. He also founded the Islamic Republic Party a week after the revolution, to mobilize hardcore supporters of the Imam.

Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani came from a wealthy landowner family in southeastern Iran and was seen as the cleverest student of Ruhollah Khomeini and his closest confidante. Rafsanjani was also a friend of Ahmad, Ruhollah Khomeini’s younger son. The older son, Mustafa, died a year before the revolution. Rafsanjani was Ali Khamenei’s closest ally. That friendship soon proved to be the future leader’s most important asset.

Rafsanjani, Beheshti, and Ahmad Khomeini saw Ayatollah Montazeri as a maverick and an idealist who could endanger the regime's survival. But they tolerated him while sidelining and executing other, mostly secular, allies of their Imam. In November 1979, young revolutionary students attacked the American embassy in Tehran and took 52 diplomats as hostages. The occupation of an embassy, seen as the sovereign territory of a foreign state, pushed many Iranian officials to resign. Beheshti, Rafsanjani, and Ahmad Khomeini, meanwhile, continued to purge the regime of their enemies.

The February 1979 revolution itself was relatively peaceful. But the new regime massacred its opposition soon after it came to power. In the weeks and months before the Shah’s fall, his army did not murder thousands of protesters, as had been expected. Many revolutionaries have told me that if the Shah’s army had used more violence, people would have been discouraged and wouldn’t have joined the revolution.

Events in Iran since 1979 show that the Islamic Republic has learned this lesson. The Shah’s army chiefs were executed on the rooftop of Ruhollah Khomeini’s residence in Tehran. Dissent across the country, in Kurdish, Arab, and Turkmen areas, was crushed violently, and political prisoners were jailed, tortured, and executed. Of course, not all political opponents were peaceful activists. Many of them were inspired by guerrilla movements in the 1960s and 1970s and wanted to take over the government by assassinating regime supporters, killing innocent bystanders, and creating an atmosphere of fear in the country. The most prominent of these groups was the People’s Mujaheddin: the MEK.

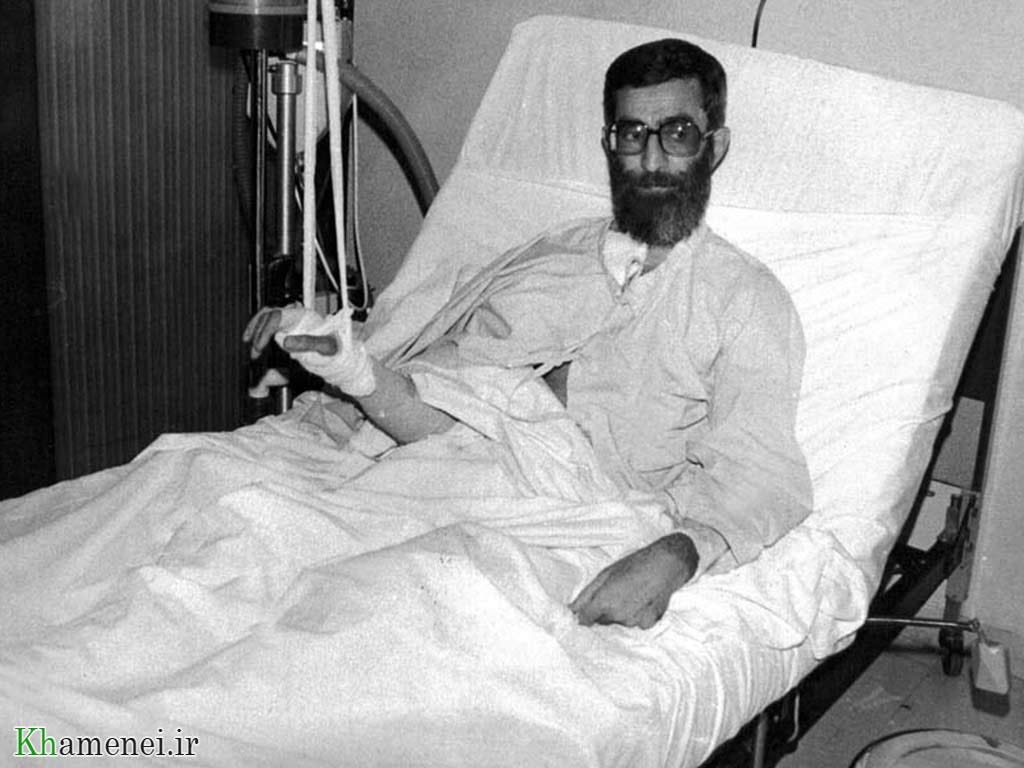

The MEK had carried out dozens of assassinations before the revolution, including six Americans. At first, they wanted to ally with Ruhollah Khomeini and even suggested that he should become president. But Ruhollah Khomeini was not in the business of sharing power, and as soon as the MEK started to mobilize its forces, Khomeini’s regime massacred its members. The MEK also killed more than 5,000 people, including many regime supporters and innocent people. On June 27, 1981, the MEK tried to assassinate Ali Khamenei. He survived the assassination, but his right hand was paralyzed for life. A day later, the MEK successfully bombed an Islamic Republic Party’s meeting, killing Mohammad Beheshti and dozens of other people.

The MEK leadership eventually moved to Iraq in 1986 and established a military camp under Saddam Hussein’s protection. The group soon became more of a cult than a political organisation. Many Iranians have never forgiven the MEK for taking refuge in Saddam’s Iraq. Anyone who believes today that Iranians could work with a foreign aggressor against the Islamic Republic needs to study what happened to the MEK.

Ruhollah Khomeini was a ruthless leader. He understood that the Shia clerical establishment may never have another chance to take power in Iran. He crushed his critics and opposition without mercy and came up with the catch phrase that has defined the Islamic Republic’s approach to governance over the past 46 years: Defending the survival of the regime is the most important religious duty. حفظ نظام اوجب واجبات است.

Ali Khamenei, meanwhile, gradually rose to public prominence, mainly because of his oratorical skills. In February 1980, he became the Imam of Friday Prayers in Tehran. Millions of people watched him on television every week, delivering sermons in which he articulated the policies of the regime on the economy, culture, and war. His favorite subject was talking about the enemy, or “doshman” in Persian. But he was never a fiery propagandist, and he continued to present a more humane face of a murderous regime.

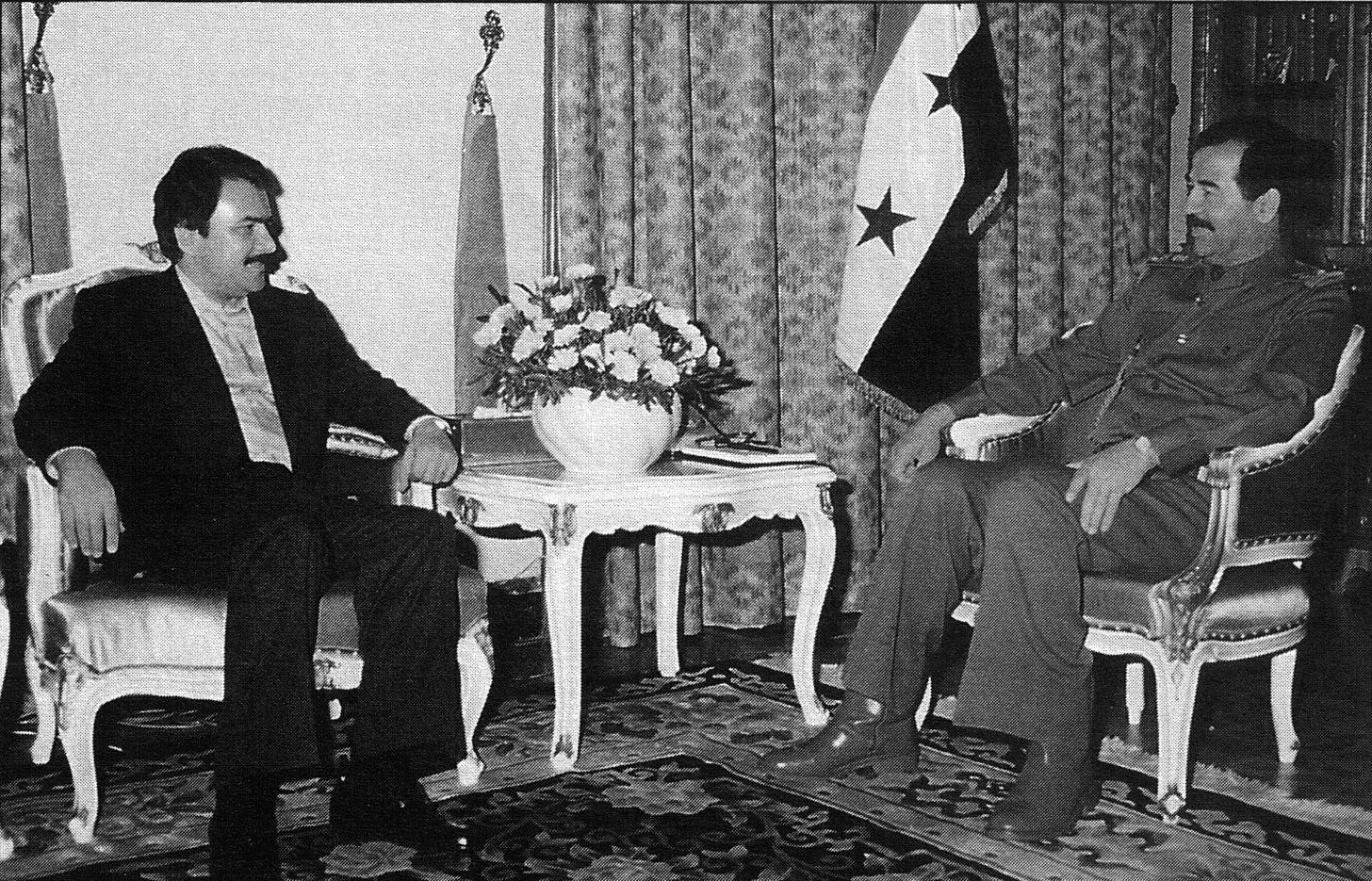

The Islamic Republic had a shaky start. Its first president fell out of favor with Ruhollah Khomeini and was forced to flee the country. The second one was killed in a bombing. Ali Khamenei was elected president in October 1981, less than a year after Saddam Hussein launched Iraq’s war on Iran. It’s important to note that Iran was not an innocent victim. Since his time in Iraq, Ruhollah Khomeini hated Saddam’s secular Ba’ath Party that had subjugated Iraqi Shias. So, after he came to power, he continued to insult Saddam Hussein and called on Iraqi Shias to rise against the brutal dictator.

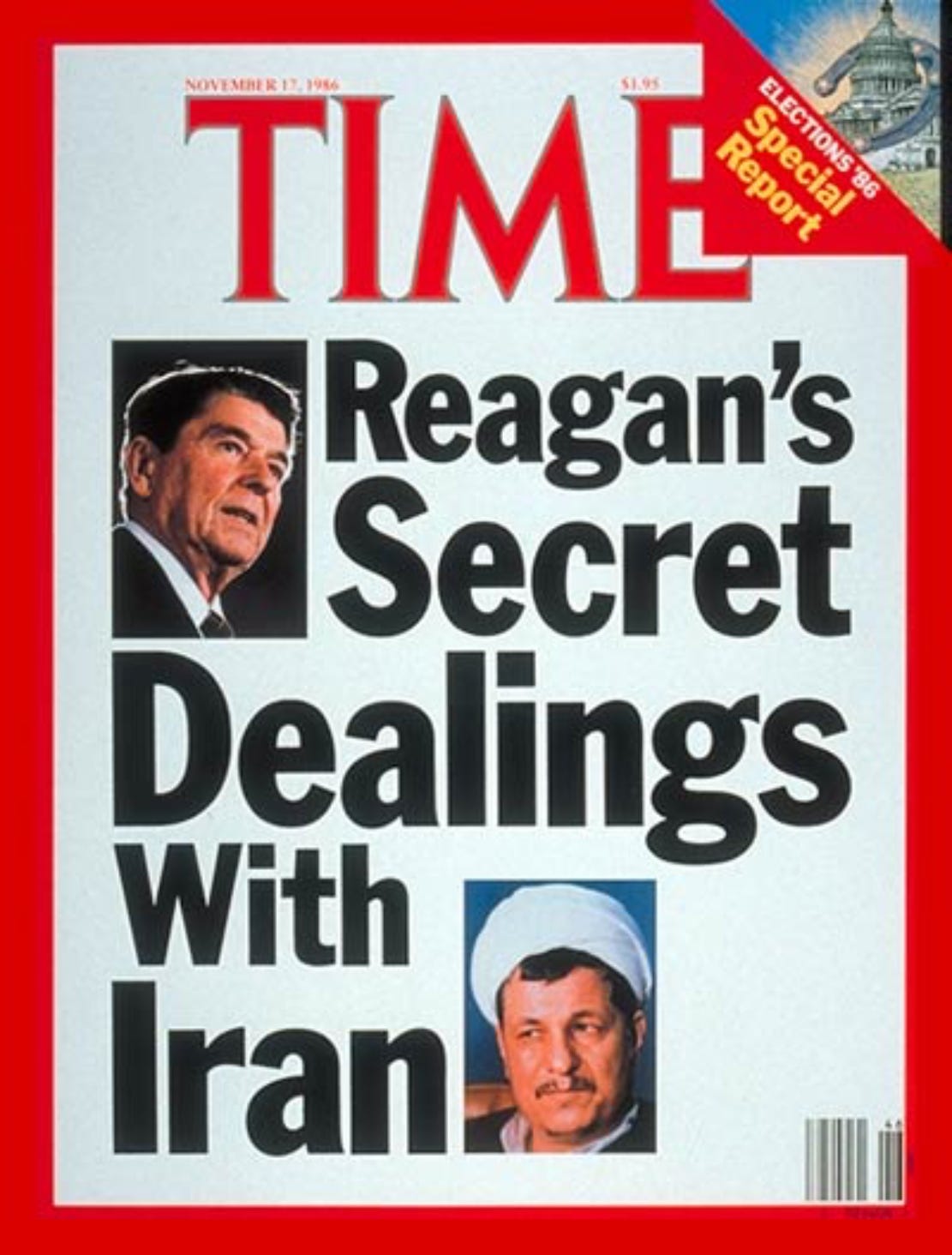

The eight-year war with Iraq was an opportunity for many politicians and clerics to show their mettle. Ali Khamenei took full advantage of it. As president, he regularly visited the front and there are several photos of him breaking bread with frontline troops. Rafsanjani, meanwhile, became the Imam’s representative in the army, and he persuaded Ruhollah Khomeini to buy arms from the United States and Israel.

Yes, Israel! In fact, Ariel Sharon, Israel’s Defense Minister in the early 1980s, wrote several letters to Ronald Reagan’s administration, criticizing the Americans for demonizing Iran, and tried to put pressure on the U.S. to allow Israel to sell American arms to Iran.

The Americans eventually agreed to the sale. The funds generated by the transaction were used to help the Contra rebels fighting the communist government in Nicaragua. According to a veteran Iranian diplomat, the purchase of American and Israeli weapons was coordinated by Rafsanjani and facilitated by Ali Khamenei. All with the approval of Ruhollah Khomeini.

Montazeri, the second-most powerful man in the regime, was unaware of the secret deals. In November 1986, a small Lebanese newspaper called Ash‑Shiraa revealed the bargain between Iran, the U.S., and Israel. The leak to Ash-Shiraa had come from Montazeri’s son-in-law, Mehdi Hashemi, a powerful Revolutionary Guards commander. He was arrested, charged with sedition, tortured, tried, forced to confess against himself on television, and then executed.

The Iran-Contra scandal led to the resignation of several officials within the Reagan Administration. It also opened a fissure between various camps within the Islamic Republic, pitting Rafsanjani and Ahmad Khomeini against Montazeri and his circle. The division soon led to an outright clash between Hossein Ali Montazeri and Ruhollah Khomeini.

Ali Khamenei, as president, tried to stay above the fray, but his loyalty remained with those who had more power; in this case, Ruhollah Khomeini, his son, and Rafsanjani.

Ali Khamenei kept quiet in the fight between the Imam and his heir apparent.

Keeping his mouth shut during that power struggle may have been the most important decision ever made by Hojatolislam Ali Khamenei – until now.

And it shaped the future of Iran and the region.

In the following article, I’ll explore events after the Iran-Contra Affair until now, and try to hopefully give you a better understanding of what Ali Khamenei may do next. By then, this may read like an obituary. Or it may not…