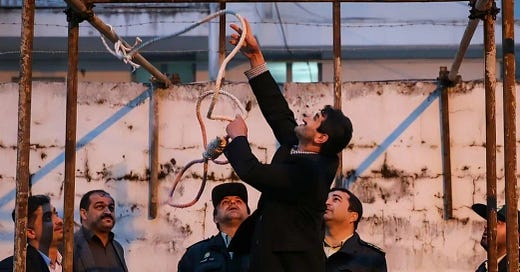

The execution came without warning on a Monday morning as Israeli missiles continued to rain down on Iranian territory.

Esmail Fekri, a young man imprisoned for two years on espionage charges, was put to death for “spying for Israel.”

The Norway-based Iran Human Rights Organization warned that Iran might speed up executions of prisoners accused of spying after Israel’s attack. Fekri was the first confirmed case of this happening.

Fekri was “sentenced to death in a brief 10-minute trial based on confessions made during interrogation,” according to the organization.

The trial took place in Branch 26 of the Tehran Revolutionary Court, presided over by Iman Afshari, with the sentence later confirmed in Branch 39 of the Supreme Court.

Fekri was forced to answer interrogators’ questions throughout all stages of interrogation and trial without access to a lawyer.

Despite having no government job or access to classified information, he confessed to charges of “espionage and providing confidential nuclear, missile, and naval information to Israel.”

Sources close to the Fekri family said the death sentence was issued only based on confessions made during interrogation under threat and intimidation.

He was transferred from Ward 4 of Tehran’s Evin Prison to Qezelhesar Prison in Karaj in February, where the execution likely took place.

The case illuminates a pattern of persecution that Maziar Ebrahimi knows intimately. Ebrahimi was one of the defendants in what he calls the fabricated case of nuclear scientist assassinations, initially sentenced to espionage and execution before being released following disagreements between two security agencies.

A sales representative for European and American audio-visual equipment companies in Iran and the Middle East, Ebrahimi was arrested and accused of espionage in a financial competition between the broadcasting organization and one of its contractors.

He endured 26 months of detention and torture so severe that he confessed to crimes he never committed.

“When you enter detention centers or security agencies, your access to everything is completely cut off,” Ebrahimi told IranWire.

“What you’ve heard about the security atmosphere, interrogation, and prison empties your heart. These things make a person extremely helpless. It’s exactly like being caught alone and helpless in a vast desert in complete darkness on a night.”

Ebrahimi lasted two months before breaking. “I was in this situation and only lasted two months. Then I wrote and confessed to whatever they said.

“Security officers often try to behave in a way that makes you feel you have no value,” he explained.

He added, “They start with psychological harassment and then, depending on what they want, they begin torturing until you finally say and write what they want.

“Apart from things they say to torment your soul and insult and humiliate you, they do everything to your body. It doesn’t matter if your skin is peeled or your bones are broken. They beat you until you finally confess.”

Ebrahimi was arrested at 1 a.m. and then transferred to the Evin Prosecutor’s Office around 10 a.m. for charge notification.

“After returning, the torture began,” he recalled. “First, several people came and said cooperate with us. I asked what do you want, and they just beat me. They beat first, and when you’re finally broken, only then do they go to tell you what they want.

“I confessed so they wouldn’t hit me with cables and torture me,” Ebrahimi said. “They would lay me on a bed and beat me with cables as much as they could. They would laugh and say your legs have become as big as your head.”

Iran’s espionage prosecutions particularly target vulnerable populations who lack the resources or knowledge to resist the system.

Edris A’ali, a 33-year-old Kurdish kolbar, is another example. He was arrested in the Sardasht region carrying alcohol and sentenced to death based on confessions his family says were forced through “severe physical torture.”

He is accused alongside Azad Shojaei and Ahmad Rasoul Ahmad, an Iraqi citizen, of espionage for Israel in connection with the assassination of nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh.

According to sources, A’ali became “a victim of security agencies’ case fabrication” due to “his ignorance and security officers’ exploitation of his lack of knowledge about legal matters.”

A’ali’s sentence was issued in Branch 3 of Urmia Revolutionary Court under Judge Reza Najafzadeh.

A source close to the Kurdish citizen revealed the tactics used to secure his confession.

“At the Urmia Intelligence Department, they told him to write and sign whatever we tell you so you’ll be freed, and he confirmed what was dictated to him in front of the camera, saying he had documents in his alcohol load that were supposed to be delivered to Israel.”

Azad Shojaei, from Sardasht and father of two children, is another case of systematic abuse.

Arrested last year on charges related to Fakhrizadeh’s assassination, he was accused of “transferring weapons, ammunition, and personnel related to Mohsen Fakhrizadeh’s assassination from Iraqi Kurdistan into Iran, under the cover of alcohol smuggling.”

Shojaei endured more than eight months of interrogation without family contact.

Under psychological pressure, he confessed to bringing two drones from Iraqi Kurdistan into Iran. His death sentence has been confirmed by the Supreme Court, and he is currently on death row in Urmia Prison.

Mohammad Amin Mahdavi, a 26-year-old with disabilities, confessed to cooperation with Israel under torture in autumn 2023.

Additional charges of “insulting Islamic sanctities” were added to ensure his death sentence, issued by Branch 15 of Tehran Islamic Revolutionary Court under Judge Abolghasem Salavati.

Afshin Ghorbani, a 26-year-old teacher and economic activist, faces execution for “intelligence cooperation and espionage in favour of the hostile Zionist regime” and “collecting classified confidential and highly confidential and secret information through unauthorized persons and providing it to the hostile Mossad service officer named David.”

The targeting of technical professionals appears in the case of Roozbeh Vadi, a former nuclear specialist with Iran’s Atomic Energy Organization who was arrested a year and a half ago.

Ahmadreza Jalali, a doctor and crisis management specialist arrested in 2016, has endured years of psychological torture through repeated mock executions.

Accused of “corruption on Earth through espionage and selling information to Israel,” Jalali has been sent to solitary confinement multiple times for execution as part of what observers call Iran’s hostage-taking policy to pressure Western countries.

The coerced confession process reaches its climax with televised statements that complete the prisoners’ humiliation.

Ebrahimi described the choreographed nature of these broadcasts: “After the television confession, the interrogations ended and the case was handed over to the judiciary for trial. I told the truth in court. I said they tortured me and I accepted my charges to escape torture.”

However, many prisoners continue their false confessions even in court. “Unfortunately, many prisoners like these people who are kolbars also confess in court because they are promised freedom and lighter sentences, while confession in court in most cases means issuing and executing sentences that can take the defendants’ lives.”

Two defendants, Naser Bekrzadeh and Shahin Vassaf, initially received death sentences that were overturned by the Supreme Court and referred to equivalent branches.

Since such branches have historically issued death sentences for similar defendants, the Iran Human Rights Organization considers them still at risk of execution.